This article appeared last year in the PM World Journal and was based on a presentation I got to give at the University of Texas at Dallas PM Symposium. For some reason, I never posted the article directly so here is “Resource Risk in an Uncertain World”.

Life is risky.

Thank goodness.

If not for the presence of risk, what would we need project managers for? We’d just make an estimate and return on the due date to pick up whatever we were building. It is risk that makes project managers so critically important to projects.

If life is risky and projects carry risk then it should be no surprise that resource management always has elements of risk. Rear Admiral Mattingly of Apollo 13 fame, once said in a project management conference, “What is a project? It is an exercise of producing a defined result with insufficient resources.” That’s almost a truism. If an organization carries too many resources, such that the risk associated to resources is zero, then that organization is almost certainly over-staffed.

In the coming pages we’ll talk about how to identify resource challenges, analyze their impact and reduce or mitigate their effects.

Overview

Resource management has so many facets, it’s important in any discussion about resources to articulate what aspect of resource management we’ll look at. In this paper we’ll be looking at the challenge to determine the resource requirements, the challenge of determining what capabilities we can bring to bear on a project to meet those requirements and finally the impact of the match between the requirement and the capabilities on this project and any other projects in the organization that may require these resources.

Establishing Resource Requirements

When we create a project and its associated tasks, we generally think of what resources we’ll require to accomplish them. The most typical place to start is to think of labor resources.

When project management systems were getting their start some 60 years ago, analyzing resources weren’t at first considered. All focus was on the critical path schedule. When it seemed apparent that not thinking of resources wasn’t helpful in projecting a schedule, the notion of defining resources was done at the most summary of skills level. It was common to find a total of 10-15 resource types in those schedules. We’ve probably strayed too far from that original concept in what is done today.

When defining the resource requirements for an element of work, you must think of the total effort required and the skill required to accomplish it. It is easiest for scheduling engines when there is only one resource type for each task, but some tasks require a combination of skills that must come from multiple resources. Effort alone is already a big improvement over just a duration for the task but categorizing the skill requirement is even more challenging.

If we think of the skill to accomplish something we often think of an ability but think about it for a moment longer and you realize that skills are often a spectrum. Someone who is a programmer is a skill. A programmer in Java; a specialized skill. A Java programmer with ten years of experience; a specialized skill with advanced experience. A Java programmer with ten years of experience and knowledge of database system. Well, you get the idea. Should we consider the skill level of our staff? Should a task that we might say would take 10 days if an inexperienced programmer were to take it on be scheduled for 5 days if a senior programmer is assigned? Perhaps. This too is an element of risk.

The same skill problem can work in reverse. What if we were only to hire extremely highly skilled resources. Then we would not have to worry about some tasks taking longer. That sounds wonderful but you are then in a situation where you are paying for senior staffers to do junior staffer roles. Moreover, think of the morale of giving a senior staff person task after task that is far junior to their skills. It would not be positive.

Getting the skills right can be a challenge and getting the resource quantity right can be a challenge. At the tactical level within a small team, this isn’t as obvious. A team lead probably knows their people very well and assigns tasks at the individual level. We don’t think much of the critical path at that level, we tend to think of a list of things to be done and who would be the best person this week to do them. It is more at the project level or the portfolio level where the skill capacity planning is a challenge and tactical decisions can affect those levels also.

Resource Utilization

While we’re talking about getting the requirements right, one challenge is often a misunderstanding of what people accomplish in a day. As project managers, we often think of the planned duration of a task and the planned resource requirement for that task and then, once it’s complete we compare how long it actually took and how much it actually required in resources. In my own experience as president of HMS Software, we have deployed our TimeControl timesheet in many different project scenarios. One theme that we see recurring is a desire to only track and manage tasks that are associated to a plan. When we ask about non-project tasks such as meetings, travel, preparation and so-on, these organizations explain that they don’t need to track those things because everyone is “on salary” so there is no impact on cost from such tasks.

In some cases in this situation we’re asked to not even track hours. “Start with the day being 100%” they explain, “then we’ll ask the resources to put in a percent of their day on project tasks and have the system ensure that it adds up to 100%.”

We ask what if someone only worked half the day. “That’s ok, the tasks should still add up to 100% of their day.”

I couldn’t disagree more.

There’s no doubt you can get some useful information from this but it belies a challenge that many in management aren’t aware of and that is the actual utilization of their staff. By utilization, I refer to the amount of time being spent on project tasks vs. overhead tasks. In some industries this is tracked by billing numbers. Accountants and Lawyers are famous for enforcing high utilization numbers. Their billable personnel should be as close to a 40 hour days as is humanly (or inhumanely as is the case sometimes) possible. New associates in particular are expected to bill high percentages of their week. Yet, even in these environments, non-billable time is rarely tracked and the result is an employee having to work 60, 70 or 80 hours in order to get their billable hours close to 40. This has the tendency to burn staff out.

Project tracking suffers from the same challenge. When we implement our enterprise timesheet and track all the time, management is often stunned to discover that their project hours are a much smaller percentage than they had anticipated. When we ask for an expected utilization percentage prior to deployment, management will confidently say that the number is certainly in the 80% range. The results are often much lower. We find it common to have utilization in the 50-60% range and sometimes worse. In one IT department we found the number to be 13% and management was stunned. There was much more to the analysis in that firm but the discovery of a project staff utilization of 13% prompted an entire change in corporate culture there.

There are many things that can take up the time where projects aren’t being worked on. Sickness and Vacation of course though I tend to discount those. Staff meetings are often scheduled and run without a thought to the cost of them. Think of the cost of having 10 or 12 people sitting around a table talking about what they are working on instead of working on what you are meeting about. Many such meetings I’ve been too have no agenda and no hard deadline and are run as though they can continue forever. Some meeting planners will take an average staff cost and have you multiply that by the number of attendees and the time allotted just to keep in mind the cost of talking.

Resource Interruption

We almost never talk about this, but the cost of interruption can be startling. According to a UC Berkeley Irvine Study[1] people spend an average of only 11 minutes on a project before they’re interrupted. Then it takes on average 25 minutes to get back to the point they were at before the distraction.

Many years ago, I was involved with a committee at Microsoft when the book Take Back your Life![2] was published. It was a how-to book on how to use Outlook more effectively. It pointed out the cost of being interrupted by Outlook notifications that pop-up on your desktop and within this group at Microsoft that was partly responsible for Outlook, all Outlook notifications were disabled. That was remarkable. At another Fortune 500 organization around the same time I was told that they were now turning off their email servers for 2 hours per day, so people could get things done instead of just responding to emails.

Unfortunately, most of us don’t structure our businesses to avoid interruption and there are many ways to do so. You don’t need to shut down your email servers to organize yourself not to be on email constantly. You can even schedule emergencies by letting people know you will be able to respond to emergency calls in a couple of hours. “Please call with urgent matters before 9 or after 11 today,” you can say.

Everyone has experienced management by emergency at least once in their life and almost everyone finds it undesirable. Aside from the stress it generates on everyone, the cost of interruption by design is almost unfathomable. Some managers like the idea of management by emergency because a) it gets them involved directly in the guidance of the project and they feel useful as a result and; b) it generates a lot of energy as people run around in emergency mode. The problem is that this is so ineffective as a management technique that the cost virtually always outweighs any perceived benefit. The best way to prove this of course is measurement.

Resource Fatigue

This brings us to the last topic on the subject of determining resource requirements and that is fatigue. When you have one or even a number of hard-charging, results-producing, take-no-prisoners project managers, you can find yourself in a situation where one project does well but the staff are near burn-out. You can only be in that kind of adrenaline-pumping mode for so long before you aren’t effective anymore.

It’s true that if project managers didn’t push for results, some projects would take longer and project managers are held to account for the result of the project even though the staff often don’t directly report to them. It’s also true that if you just let resource managers schedule work, they would spend much more time on staff training, time off, managing staff well-being and not being as committed to a particular result. So, a balance between the two is often the most effective but for project managers if you are now looking to schedule personnel and you live in a world where the staff are in fatigue mode all the time, you may need to allow for that in your schedule. Worse, if you are in an organization where this kind of mode is commonplace, you may find you have to deal with a high rate of staff turnover. Having new staff coming in and experience staff rotating out all the time is a costly impact on every project.

Eliminate or Mitigate?

Those are just at taste of the resource risks and challenges we face. Should we seek to eliminate the risk or just mitigate? The answer is: It depends.

Of course we would like to have less risk but the cost of eliminating risk is almost certainly too high for most. Let’s look at the challenges project managers face in trying to eliminate risk.

Skill mismatching

There can be good reasons for deliberately taking on projects for which the skills sets of your resource pool are mismatched. For example, if the organization has decided that it must generate skills in a particular area. Perhaps there is new technology emerging and the organization could get a competitive advantage by developing skills in that technology. The results will be ineffective compared to other opportunities in the short term but holds the promise of much more productivity in the longer term.

If the skills of the work you are managing are a mismatch to the work you are doing, you should be able to articulate the cost and the long term benefit of that mismatch. If you are not able to do so, it’s worth pausing to see if your project selection process needs work.

Beware of hoarding

We’ve already discussed the difficulties in ranking resource skills and the time it takes one person to do something versus another. One possibility that occurs when key skills are scarce is to hoard them. Imagine you are a project manager who has just started on a new and complex project. You know that at some point in the project, having access to a particular person will make a critical difference to the project’s success. Yet you may not be certain when that moment will come only that it will come eventually. The best way for you to ensure surpassing this crux in the project is to get that person assigned to your project for as much of the project as is humanly possible. You assign them to tasks of almost any nature until the critical one you’ve been planning for arrives and then you can release him or her back to the general pool of resources. This may be a great way to ensure the success of this project but it’s also a great way to make other projects unsuccessful. This type of pitfall comes from the very best of intentions at the tactical level by project managers but can have far-reaching negative effects on the efficiency of the entire organization.

Eliminate the risk by just adding more

Resource levelling could presumably be solved by just adding resources until the overloaded histogram isn’t overloaded anymore. This is often the request of project management personnel who are sure they can’t get the work done that they are responsible for.

Just adding staff is rarely successful however. Think of the challenges. First of all, if you are hiring and on-boarding more employees, there is an overhead cost to bringing on new people. This will also affect existing staff who have to devote some of their time to helping new staff become acclimatized. Whether you are using salaried staff or offshore contractors, supervisory duties for those new resources must come from your existing resource pool and no matter how experienced they are, they aren’t experienced in your business yet. So a ramp-up time will be required. If you are moving from in-house resources to off-shore resources, you should be factoring in the cost of managing those resources, of communications over long distances and of doing more design in-house in order to support the new external resources. It is rare that using remote resources in this way will make a short term difference. In the long term, finding skills remotely which are more affordable can make a difference to the bottom line, but at a cost of more management internally.

Beware of Resource Levelling Individuals

For many years, project and portfolio management systems have touted the benefits of making the project management systems available and a part of every employee. The demonstrations done to organization after organization showed everyone getting a dynamic view of their own tasks and their progress being reported up from the front line workers to the top end management. This necessitated of course, the management of resources at the individual level. The challenge with this is that resource levelling algorithms don’t level individuals. They were designed to level large bodies of resources which were more generic in nature.

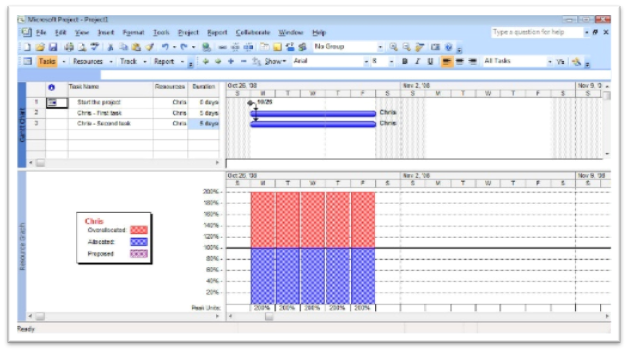

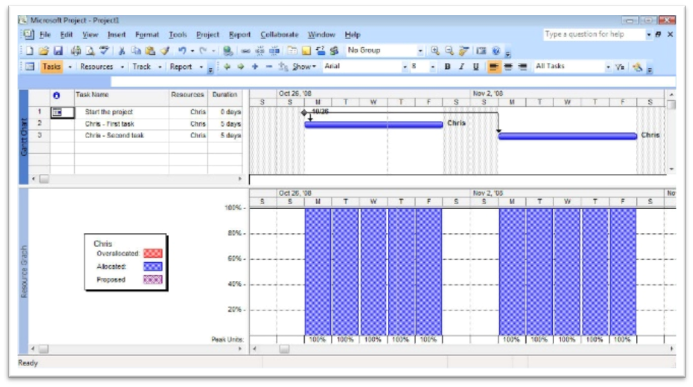

Consider the following simple problem:

A single project has two tasks and one resource. Each task is a week long. The tasks are resource leveled. No surprise, the work will now take two weeks.

But resource leveling happens within the critical path calculation. When we add 7 more days of work and a second resource, you would expect to end earlier.

Not so.

Now, not only does the work push into week 3, but the second resource will not have any work at all in the second week.

It is examples like that has had large project management software vendors de-emphasize their resource leveling algorithms.

Resource leveling in modern project scheduling software is inappropriate. This may also be why there has been a new interest in transaction project allocation systems based on Agile methods where the critical path is de-emphasized.

Real Time project management? Myth or Reality

Some organizations will attempt to deploy so-called “real-time” project and resource management tools. The notion is that if management were involved in real-time decisions, resource conflicts could be largely eliminated or, at worst, quickly resolved.

The challenges to real time project and resource management are vast. To start with, what does it mean? If we were to update resource conflict displays every 5 minutes, would management be prepared to make resource decisions every 5 minutes? Probably not.

We also make numerous assumptions about project and resource data displays such as dashboards. We presume that the data has been approved. Are we ready to approve project and resource data every 5 minutes? We presume that the data is timely. There is little point to making a decision about data in which part of the data was updated 5 minutes ago and the rest was updated a week ago. We presume the data is complete. We presume the data is relevant to the rest of the display. Particularly with project data, the update of one task can affect every single other task in the project. Is it appropriate to show the update of that task without showing the updates and/or impact on any related tasks?

Ignoring risk carries its own costs

Some organizations try to eliminate resource risk by wishing it away. They decide they will simply not measure or manage the problem and push the responsibility for it to subordinates. Just like an ostrich burying its head in the sand to avoid danger, this technique does little to avoid the risk. It simply displaces the blame for the all-but-certain bad results.

Mitigate the Risk

In the end, eliminating resource risk is probably a fool’s errand. Life is risky. Perhaps we should mitigate instead.

Avoid Micromanaging Resources

One of the first lessons experienced resource managers learn is not to do it all. Trying to micro-manage from the top of the organization all the way to employee’s individual to-do lists is virtually never successful. It’s an easy and impressive software demonstration but there are fundamental differences between a high-end algorithmic perspective of the organization’s projects and the commitment-based to-do lists or tactical agile task management systems which makes up people’s day. Instead of that plan, make a top-down analysis of resources at the portfolio level and let project managers do more skill-based planning at the project level. At the tactical level, let team-leads use tactical tools to assign work to the individuals. I remember a consultant from many, many years ago saying to me “It looks integrated, but it isn’t integrated”. That can be a worthwhile structure for this type of challenge. Apply the appropriate type of tool at each level. The benefits to having all that data from different levels of the organization centrally connected when the processes around them were very different is, at best, questionable.

Start tracking at the person-day instead of skills

One of the most successful portfolio management processes I helped a firm create started with project schedules that had only person-day requirements. There was tremendous push-back from the parties involved when I proposed it but my comment to these senior managers was “If you can’t do portfolio resource prioritization at the person-day level, what hope do you think you’ll have working at a high-end skill level?” That was enough to mollify them into participating and, I was correct. Even with just a number of person-days per project, we had big challenges to overcome in prioritization. I remember getting through our first couple of high-end analyses and having the President of the organization say to me, “But this isn’t even as bad as it is. This is a blue-sky-pretend-all-resources-are-perfectly-aligned schedule.” “Correct,” I replied. We have a bunch more work to do than just fix the capacity problem.

Eliminating the added complexity of full skill definition made the process easier and let the organization focus on challenges it could make a difference on. It was an interim step to be sure but starting from simplest and moving towards more complex is always a good operating principle. Focusing on too much detail carries its own risk and often ends up in a situation where disagreements over how skills are defined and who should get access to certain skills overshadows other elements of the resource management process that might have otherwise been resolved.

Centrally track only the key resources

Here’s a method of quickly improving resource management performance for organizations which have struggled with deploying a centralized resource management process. First, identify your most key resources. This is usually a handful of people (No more than 5-10) who have particular combinations of knowledge, skill and experience that makes them essential for certain tasks. If you are wondering who these people are, they are the same people you thought of when we discussed hoarding of resources a little earlier. Next, create a single schedule which will be managed centrally in which only the tasks for those people are managed. Finally, let all other skills be organized at a more tactical level by team leaders. They can use whatever method of resource allocation they’ve always used.

In our experience, this method has a long history of success in the short and medium term. It focuses attention on critical tasks that can only be accomplished by the most experienced and skilled resources. It keeps projects moving around these key resources. It eliminates trying to hoard or hide skilled resources. Finally, it reduces stress and emergency management of your most valuable people.

This isn’t a replacement for long term strategic thinking on resource management or implementing good portfolio selection and good resource tracking. But, as an interim solution, it can deliver results almost instantly.

Implementing Change

Change causes upset. It just does. Anyone who has looked to change corporate policy in any way has run up against resistance of inertia of existing practices.

Some may think that that best method of overcoming such resistance is brute force. Find the executive at a senior enough position to hold real power and force individuals to comply. This is rarely successful. When you are managing change, the end result has to be people who are working together. Regardless of what methods we’ve described above to mitigate resource risk, finding a way to implement those changes will be just as important as determining what to change. Here are a few tips to avoiding disaster even with the right plan.

First of all, don’t try to change everything at once. Think in an Agile fashion about change management. Pick one or two of the most influential methods or, pick one or two of the easiest to swallow methods and implement those. When some time has passed, and those changes are now part of the landscape, think about deploying another change or two. You may never get to all the changes you want but the return on your investment will happen much, much faster than trying to implement everything you want at once.

Next, look for pockets of the organization where what you are doing is already working. Is there a department or group that has successfully implemented one or more of the methods you’re considering? Enlist their help as allies in spreading that practice to others. Two things will happen through this. First, you won’t have to change that department. They’re already doing what you want to be doing. Second, you will find the morale of those people very high in this endeavor as it’s flattering to highlight what you’re doing that’s effective. This approach can deliver huge momentum to any change you are considering.

My favorite method of implementing corporate change comes from American inventor and visionary Buckminster Fuller which he referred to as “Trim-Tab”.

Fuller pointed out that on a large ship such as the passenger ship the Queen Mary, the direction of the ship is determined by the rudder but the force needed to move the rudder can be enormous. So marine engineers came up with a concept called a trim-tab. It is effectively a tiny rudder at the back of the rudder. When the rudder needs to move, the trim-tab goes in the opposite direction. Think of it being a rudder for the rudder. It can be pushed with a force as small as the pressure of your hand and the result is the entire rudder turns and, because the entire rudder turns, the ship itself ultimately turns.

I don’t know if Fuller cared much about the Queen Mary but he cared greatly about changing organizational thinking; organizational culture.

In project management terms, we can find tiny changes in process that ultimately change the direction of the entire organization. For example, deploying a central schedule for just 5 people is an innocuous request. It doesn’t appear on its face to be an attack on anything. After all, there are hundreds of resources. But the central management of just those five people can ultimately affect the effectiveness of all projects.

That’s a trim-tab.

Conclusion

There is probably no number of pages that would be sufficient to completely encapsulate the challenges of resource management and the risk that requires it. In this paper we’ve considered several aspects to resource risk.

Start by identifying the problem. It’s commonly said that a solution needs a problem. So make sure you can articulate your problem with resource risk before creating solutions to solve it.

Next, avoid the pitfalls of trying to eliminate all risk either by just hiring and hiring or by avoiding the challenge altogether. Instead, look to avoid risk where possible, reduce otherwise and mitigate the effects where risk is certain to remain.

Look for opportunities to mitigate risk by looking at the bigger picture and separating strategic, functional and tactical levels of analysis into separate processes. Remember it’s sometimes better to look integrated than be integrated.

Finally, be sensitive to how you implement change. Change will cause upset. Work in small steps rather than sweeping procedural replacement. Finding small changes in procedure that ultimately change organizational direction can make a difference while not exceeding people’s comfort level. Think Trim-Tab.

[1] https://www.ics.uci.edu/~gmark/chi08-mark.pdf

[2] https://www.amazon.com/Take-Back-Your-Life-Microsoft%C2%AE/dp/0735620407